Recently I encountered an SF novel in which medical care—more exactly, healthcare funding—featured as a significant element. Curiously, the work drew on the same rather implausible healthcare system used to such effect in, say, Breaking Bad. No doubt the author was simply unaware of other approaches. Other science fiction authors have been more imaginative when it comes to healthcare systems, as these five examples show.

Note that authors favour plot-friendly factors over other real-world criteria for health systems. A reliable rule of thumb is that the more user-friendly a medical system is, the more likely that it will be relegated to the background—James White’s Sector General series being a notable exception. If medicine is as cheap and convenient as brushing teeth, odds are good that medical issues will consume as much plot time as brushing one’s teeth…

One way to sidestep the constraints of supply is to somehow automate the process. If one can make the mechanisms responsible for keeping people healthy self-replicating, so much the better. At least, that was the thinking that led to the setting of Mira Grant’s Newsflesh series—Feed (2010), Deadline (2011), Blackout (2012), Feedback (2016), and Rise: A Newsflesh Collection (2016).

Doctors Wells and Kellis set out to create engineered viruses aimed at eliminating cancer and the common cold. An unscheduled, unsanctioned field test revealed that their creation was wildly successful…in the sense that neither cancer nor the common cold was anyone’s primary health problem once the virus spread. Pity about the global zombie apocalypse that followed, but you can’t make an omelette without breaking some eggs!

***

In Project Itoh’s 2008 Harmony, an Earth shaken by the Maelstorm—pandemics exacerbated by nuclear war—rejected death and war and embraced “Lifeism.” “Admedicstration” facilities monitor the Earth’s population, providing humanity with individualized advice and treatment designed to optimize each person’s quality of life as defined by Lifeism. Opting out is not an option—but loss of autonomy is surely a small price to pay for perfect health (even if one had no say in the criteria for the alleged perfection).

At least, that’s the position taken by the people running the world. They might not be terribly surprised to discover that there’s a minority who want to escape the admedicstractions. They would be astounded to learn how the malcontents plan to elude a modern world they find abhorrent. But not for long.

***

Americans enjoy universal healthcare at a cost in Alan E. Nourse’s 1974 The Bladerunner. Afraid that routine access to free healthcare would lead to an enfeebled, genetically second-rate population, the government added a non-monetary price to the use of the healthcare system: mandatory sterilization. The reasoning: those requiring medical care would not pass their genes on to the next generation. This bold strategy created a population highly averse to sanctioned healthcare, as well as a thriving black market in illicit medical care. Alas, there is just one tiny flaw in the system: it destroyed any plausible way for the government to protect the population from a novel pandemic. Which leaves only the bladerunners standing between Americans and mass death.

(My apologies for mentioning a book with such an unlikely plot. No government would be so foolish as not to have a constructive plan for combatting a pandemic.)

***

After centuries of resource depletion and nuclear war, Earth is an impoverished ruin. This is the setting for Vonda N. McIntyre’s 1978 Dreamsnake. The only medical care comes courtesy of wandering healers like Snake. Assisted by her extraterrestrial serpentine pets, the eponymous dreamsnakes, Snake can heal many human ills and offer painless release to patients she cannot heal. But cultural misunderstanding leads to disaster and the loss of a precious, irreplaceable dreamsnake. With her status as a healer at stake, Snake must seek out a replacement at Center, Earth’s remaining metropolis. Corrupt, hierarchical, cruel—the people of Center are many things, but charitable is not one of them.

***

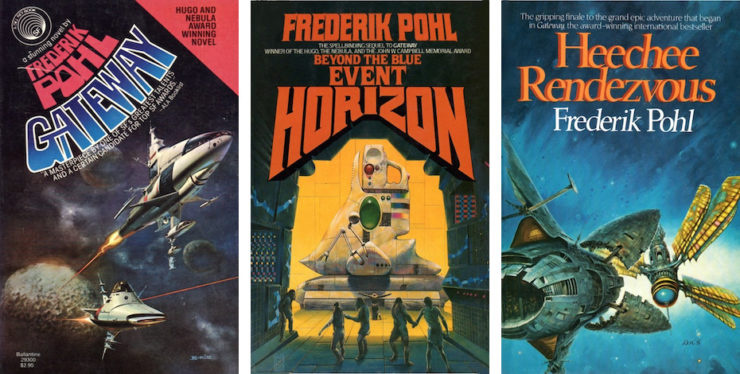

Frederik Pohl’s Heechee series—Gateway (1977), Beyond the Blue Event Horizon (1980), Heechee Rendezvous (1984), The Annals of the Heechee (1987), The Gateway Trip (1990), and The Boy Who Would Live Forever (2004)—is a literal illustration of Marx’s “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.” The wealthy need perfect healthcare, which requires an endless supply of transplant organs. The poor can provide said organs. Economic despair inspires sharing when mere public spirit might not. For many of Earth’s desperate poor, literally selling themselves is the only way to support their families: Demand and supply!

***

No doubt you have your own favourite examples of fictional healthcare systems, and no doubt I failed to mention them. The comments section is, as ever, below.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is a four-time finalist for the Best Fan Writer Hugo Award and is surprisingly flammable.